What is with this obsession with the idea that science can somehow explain who we are as people?

I’m not exactly above it, I suppose. There was a period when I was considering doing 23andMe because I wanted some Scientific Confirmation™️ of my ethnic heritage (I ultimately held back because I’m cheap and had privacy concerns; and recent hacks of the company’s database have only made me feel better about that decision), and, like many folks, I have a smart watch that tells me my biometrics, which is how I know that my resting heart rate spiked early in my bout with COVID (it’s back to normal now).

But when it comes to looking for some scientific basis for my sexuality, I have always been left cold. I’ve never really understood why I need science to “confirm” that I’m bisexual; not least because the notion that science can somehow confirm my sexual desires also suggests that it might be able to refute them as well. If there’s a “bi gene” and I don’t have it, does that mean the arousal I’ve felt during sexual encounters with people of different genders is somehow invalid? I would rather just trust myself.

So I have to admit feeling a little baffled by the line of argument that unfolds in Alexandra Shimo’s Walrus essay titled “The Science of Late-Blooming Lesbians,” a headline which raises far more questions than it answers. What, exactly, makes a lesbian “late-blooming,” for instance? And, more importantly: they have a science for that?

Well, no. What the essay expresses is not so much a scientific explanation of why more lesbians than gay men first realize that they might be queer after the age of 20 (which seems to be what is considered “late-blooming” here), but rather a desire for science (“science”) to find a way for lesbians to figure out that they’re lesbians ASAP, in order that they might live their truest, happiest lives as early as possible.

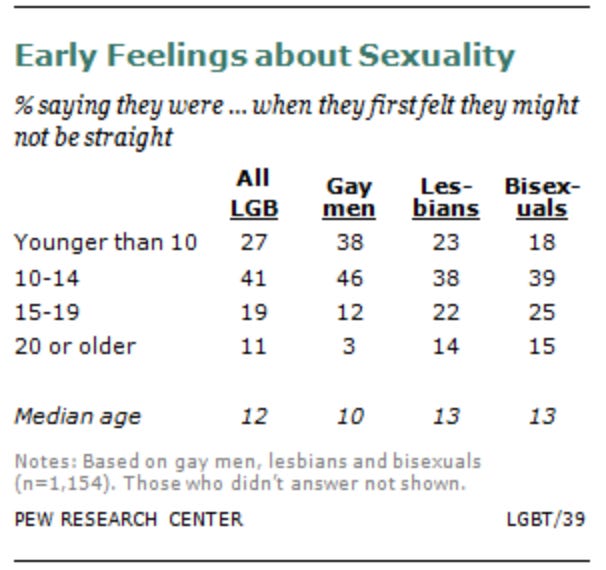

I have to stop for a second and nitpick a few things here, though. First, let’s pull up the Pew Research Center data that seems to form the, uh, scientific core of the notion that lesbians are somehow more “late-blooming” than others.

Here is the way that Shimo frames the findings within her essay:

Citing scientific literature from the 1970s and ’80s, Rust noted that “research on gay men indicates that they experience [homosexual arousal] at younger ages and more rapidly than lesbians.” More recently, Pew Research Center broke it down by age. A study published in 2013 reported that 38 percent of gay men first sensed they might not be straight when they were younger than ten, compared to 23 percent of lesbians. Fourteen percent of lesbians said they first thought they might not be straight when they were in the oldest category—age twenty or above—compared to 3 percent of gay men.

And here is the table from the Pew Research Center study.

Do you notice that, perhaps, Shimo may have left something out? In her rush to wring her hands over the poor long suffering lesbian late bloomers, she’s utterly removed bisexuals from the equation. Once we’re factored in, lesbians don’t seem like the lonely late blooming outliers — to the contrary, it seems far more that gay men are earlybloomers with a precocious ability to recognize that they’re just not into women while lesbians and bisexuals are still fumbling through the world trying to figure ourselves out. And yet even still: the median age for both lesbians and bisexuals first feeling they might not be straight is… 13. You know, right about when people start having sexual feelings in the first place. A pretty appropriate time for a queer awakening, one might say.

Muddying the waters further are the three celebrity examples that Shimo brings up to illustrate the narrative of the “late-blooming lesbian”: “Meredith Baxter, Portia de Rossi, and Cynthia Nixon.” Of these three, Meredith Baxter — who has publicly said she didn’t realize she was a lesbian until her fifties — seems like the only actual “late-bloomer.” Portia de Rossi was much more a classic self-hating closet case who emphatically didn’t want to be a lesbian, while Cynthia Nixon — who weirdly gets mentioned a lot throughout this piece on late-blooming lesbianism — is bisexual. The idea of these three women as stunted lesbians in need of science to help them figure out their shit is just… bizarre. De Rossi needed therapy, queer role models, and a world that told her it was okay to be gay. Cynthia Nixon may never have had a queer awakening if she hadn’t met her wife — who seems to be the main and perhaps only woman she’s ever been attracted to. Could science have helped Baxter? Maybe, but also maybe she, like de Rossi, just needed to be in a world that made lesbianism seem more okay. (Seems telling that she “bloomed” right as lesbianism was becoming more socially acceptable!)

So already this all just feels more complicated, right? The narrative of the lesbian who simply doesn’t realize she’s sapphic until way later than everyone else has figured their shit out may be a deeply rooted one among queer women. But that does not automatically mean that that’s inherently what is going on.

Especially, since, well — I have to go back to this whole entire notion of “late-blooming” as even being a thing, I think. Shimo winds up spilling a lot of ink talking about research into female sexual arousal, arguing that perhaps the documented tendency for cis women* to be sexually aroused broadly, even by stuff we’re not mentally into, might be part of the reason why lesbians just take so darn long to realize they’re not into men, but the ultimate core of her piece seems to be this:

In many classic movies and books about lesbians, the climax is the moment when the protagonist lets go of society’s shame to become her true self. Can research expedite these moments of awareness so we can live the way we want to live sooner?

Ah friends, there it is: the true self.

There is this common obsession — among queers, certainly, but not only — that there is a “true self” within us that is waiting to emerge. The “late-blooming lesbian” carries a lesbian seed within her that wants to erupt into a flower as quickly as possible. Every relationship you have that ends is somehow just a part of the lead up to your “one true love,” without whom your life cannot truly begin. There is this idea that life is a process of whittling away excess wood in order to reveal some most correct version of who we are that’s lying just beneath the surface.

And friends, I simply don’t believe in that “true self.”

I mean, yes, of course I believe that queer kids should be given the space and resources and support to explore their queerness from a young age. And I believe that trans kids should be given social support and gender affirming care as well. I believe that being able to explore queerness and gender identity in a supportive environment from a very young age makes people grow up stronger, happier, and more confident.

And yet I also believe that even within an environment like that, there will still be people for whom queerness or transness doesn’t emerge until later in life, not because they have spent years in the closet, but because the very nature of their understanding of themself has simply shifted over time. There are people for whom there is no fixed “true self” — and we are not “late bloomers.” We are simply people for whom life is an exciting journey, the end point of which will remain a mystery until we die.

I do not need, or want, science to tell me who I “really” am. I do not think it has that capability, anyway. I’m sympathetic to Shimo’s belief that something out there could have helped her tap into her queerness early on, that something could have helped her skip all the boring boyfriends and go straight to the pursuit of women as soon as she had her first twinges of adolescent sexual desire. But maybe that belief is a misguided one. And maybe that’s not so bad. Maybe dating women in high school wouldn’t have automatically made her life any better, happier, or more fulfilling.

And maybe the journey that she did have made her appreciate her eventual wife all the more.

* Maybe trans women too, it’s probably an estrogen-related thing, but I don’t think anyone has studied this phenomenon in trans women

Leave a Reply